Who was Masanobu Fukuoka?

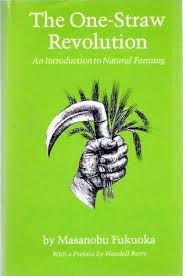

Masanobu Fukuoka’s book The One-Straw Revolution* was published in 1975. Those who embraced the swift advances in technology of that time, especially in agriculture, dismissed it as the work of a crank; those who questioned the impact that agribusiness had on the planet and loved nature for itself, embraced it, and Fukuoka inspired devotion amongst his followers. One such, Larry Korn,** an Asian scholar and soil scientist, brought his ideas back to the US after working with Fukuoka on his farm for several years.

The One-Straw Revolution was Fukuoka’s first book and in it he sets out his beliefs about how to farm, live and eat. Written when Fukuoka was 61, the book begins with a brief account of why he turned his back on a career in plant pathology some thirty five years earlier. He had been studying in Yokohama under a professor he found inspiring, pursuing specialised research into a fungus that infected citrus trees-highly focused work in which he was “struck by how similar this minute world was to the great world of the infinite universe”. Then he fell ill with pneumonia, and after recovering physically, he became depressed. One night, aimlessly wandering in the hills above the city, he collapsed with exhaustion and slept. On waking he watched as a night heron flew over the water below, and this sight brought on an overwhelming sense of joy and transcendance. In the same moment he describes how he cast off all his previous beliefs in favour of one truth. As Fukuoka puts it, all of a sudden he understood that it was impossible to ‘know’ anything through using our intellectual capacities, as he had been doing in scientific research.

He put this new found faith into practice straight away, resigned from his post, and returned to his family’s citrus farm, to devote his life to practical farming. But he had not abandoned the scientist’s desire to provide empirical evidence for his assertions: from then on he made it his life’s work to test his new belief in ‘natural farming’ and to demonstrate to the world that it was just as productive as science-driven agriculture.

I struggled to fully appreciate what Fukuoka was getting at philosophically until I had read the whole book, which includes regular digressions into his spiritual ideas. As I understand it, his ideas about nature and life are similar to Buddhist precepts, which contrast strongly with Western habits of dualistic thought and a high regard for rational argument, human intellect, science and materialism. Fukuoka saw people as firmly embedded in cycles of life and with no right (let alone duty) to dominate nature or to take from it more than they put in. Moreover, he believed that the human mind is not properly equipped to understand the mysteries of nature. On the more practical side, he was clearly shocked by the speed with which Japanese farmers were abandoning ancient agricultural practices in favour of an agribusiness model after the second world war. Above all, perhaps, he believed that the contemporary attitude that nature could not provide enough food for people without huge technological input, was simply wrong.

The ‘Natural Farming’ Model

With this background, Fukuoka set about designing his own ‘natural farming’ model. He lived on the island of Shikoku, southern Japan, in a sub-tropical climate where the main crops were rice and mandarin oranges. If I describe his farming year, it should give a good idea of what he was trying to do, and also explain better what he meant by his four ‘core principles’ of farming.

So, to start with in his typical rice field***, he would not undergo the usual cultivation associated with preparing the ground for planting as in a British arable field. In fact our concept of a ‘linear’ year beginning with preparation for planting and ending with harvest has to be set aside as in Fukuoka’s mind the year was fundamentally simply an annual, repeating cycle. Indeed his first core principle is ‘NO CULTIVATION’. Hence, I will just jump into the cycle at the point when rice seeds are planted, end of April/beginning of May. At this time, rye or barley plants would already be growing in the field, and the rice seeds would thus be broadcast (by hand) amongst the young plants, along with some white clover seeds. The clover seeds reflect Fukuoka’s second core principle of ‘NO CHEMICAL FERTILISER OR PREPARED COMPOST’, the clover being intended to provide a green manure to feed the young rice plants. In May, just after planting the rice, the rye or barley is ready for harvest, which in Fukuoka’s method, is done by hand. Then the rye or barley straw is spread back over the field with a little poultry manure to aid its decomposition, and act as an additional natural fertiliser of the young rice plants.

Then, in October it is time to plant the winter rye or barley in amongst the ripening rice plants (more white clover having been sown just before if necessary). Soon after this it is time to harvest the rice (again by hand) and -again- scatter its straw over the winter grain seedlings for the reasons given above. Over the winter months, the winter crop remains in the ground and little work is carried out in the field until the cycle begins again in the spring. Readers will not be surprised by now that Fukuoka’s fourth core principle is ‘NO DEPENDENCE ON CHEMICALS’. Fukuoka sought to create “a balanced rice field ecosystem’, and pest and disease problems were rare. His main pest challenge was surprisingly mundane-sparrows! To stop them eating seeds broadcast in the field, he hit upon the ingenious (and labour-intensive) solution of coating the seeds in clay pellets, which would break down gradually in damp conditions allowing the seed to germinate. So there is no doubt, I should perhaps include a fifth principle not articulated by Fukuoka: no tractors.

Fukuoka applied similar principles to the growing of various orchard fruits and vegetables: in fact, he went one step further with vegetables by interplanting them in the grass beneath the orchard trees and even on the mountainside (“growing vegetables like wild plants”).

Natural farming today

This carefully planned and labour-intensive approach to farming was successful in terms of yield and quality as well as soil fertility compared with crops grown conventionally. Ecologically minded farmers since Fukuoka have assimilated some of his practices. For example under the organic system there is no use of artificial fertilisers, pesticides or herbicides, and permaculture seeks to maximise production on a unit of land without harming the environment. Fukuoka’s farm was very small by modern standards and his heavy reliance on manual labour makes the system untenable on most farms now given the cost (and challenge of finding) agricultural workers. Many famers would no doubt also question how weeds could be controlled without cultivation or crop rotation. However, behind Fukuoka’s four core principles I take one over-riding key message. When a farmer recognises what nature has provided them with in their parcel of land, in terms of soil, climate, possible crops and feasible livestock, then they can work with nature for the benefit of the wider environment and their community. They may even have enough leisure time for creative pursuits as did their Japanese forebears whose haiku appear on the walls of Fukuoka’s local Shinto shrine!

Fukuoka and farming politics

As is clear Fukuoka believed in nature’s own balancing and fertility providing capacities, and he questioned the value of science when it is applied narrowly to sort out one problem without reference to the wider context of other plants, animals and climate: “an object seen in isolation from the whole is not the real thing”, he argued. Fukuoka’s commentary on the politics and economics of agriculture were also prescient and remain relevant today. He asserted robustly (and made enemies in the process) that economic and political self-interest dictated the actions of chemical companies (supported by government), as much as belief in the science and efficacy of their products. He observed that their influence had forced many Japanese farmers out of business, leaving those remaining abandoning traditional methods for new that rendered them just “ a factor in modern agriculture’s equation of increasing speed and efficiency”. Where they had remained in tune with nature’s cycles (and limitations) they now found themselves working frenetically, at the whim of agricultural salesmen, commodity markets and capricious consumers.

His methods posed an alternative that relied on the farmer’s understanding of his land and the input of human labour and he showed that it was possible to produce a wide range of foods, especially where the emphasis was on producing little meat but plentiful vegetables, grain and fruit.

Fukuoka and food

Fukuoka turns his attention to food in the second half of the book, beginning with regret for how barley (a crop very suited to Japanese conditions) was forced out of production by imports of cheap American wheat. He also regretted how people then abandoned a “natural diet” of grains (particularly brown rice) that had co-evolved with humans over thousands of years of farming. To attempt to convey his idea of natural food he includes two mandala (similar to a flow diagram and a pie chart) identifying links between various farmed and wild foods in his environment, and their seasonal supply. To eat simply from a range of these foods, cooking simply with just the addition of salt, seemed to him to tie an individual to their environment and a community to each other in a way that conferred spiritual benefits as it reflected unity with the natural processes. He also stressed the importance of local supply and in his view “a community that cannot produce its own food will not last long”.

Some of his ideas can be difficult to grasp-for example when he contrasts intellectual “discriminating” knowledge and natural “non-discriminating understanding”. He disapproved of the random search for new flavours or food experiences, regarding it as evidence of how “food and the human spirit have become estranged”. “People nowadays eat with their minds, not their bodies”, he argues, and as food directly links to spirit and emotions our diets should never be approached as simply a materialistic solution for our physiological needs. Whilst his prescriptive discussion of four types of approach to food ranging from the bad “lax diet” entirely based on tastes to the best “natural diet” can feel a little obscure and puritanical, Fukuoka does forcefully remind us that food and farming are inextricably linked: “the front and back of one body”.

What is Fukuoka’s legacy?

Sometimes the pressures in modern agriculture and food production can seem an insurmountable obstacle to change. But Fukuoka’s life and work set an example. Whilst he was alive, he travelled and shared practices to re-vegetate land suffering from desertification. He continues to inspire many in sustainable agriculture and food and I know of at least one professional chef whose view of food is shaped by The One-Straw Revolution. Personally I was moved and challenged by his powerful emphasis on growing and eating in tune and time with nature, both for individual health and spiritual well-being as well as healthy communities. I don’t think many of us could follow the life of manual labour and extremely simple living and eating led by Fukuoka himself and his largely voluntary workers on the mountainside in Shikoku, and we would be hard put on our farm to adopt some of his practices. But he clearly lived well (and long), farming successfully in defiance of those most influential in world agriculture. Reading this book has left me with renewed energy to seek ways of living and working that get closer to Fukuoka’s ideals.

More Information:

*Masonobu Fukuoka, The One-Straw Revolution, New York Review of Books, New York 2009 (originally published in Japanese, Tokyo, 1978) includes introductions by Larry Korn (editor) and Frances Moore Lappe, and a preface by Wendell Berry

** You can read more about Larry Korn and his work in sustainable agriculture at http://www.onestrawrevolution.net/One_Straw_Revolution/Larry_Korn.html

*** It is also interesting that Fukuoka did not grow rice with standing water in his fields. He did hold monsoon rain in the field in June to control weeds, and then he ran water through the field during August but otherwise the rice grew without artificial irrigation (54-5).