The past decade has seen consumers develop a taste for single-origin coffee, “premier cru” cider and mineral water with a “terroir”. Phoebe Weston meets a new breed of carnivores who believe 100% pasture-fed meat is the way forward.

“It’s very nutty”, says the lady at the end of our table with an empty fork in her right hand. Her neighbour nods in agreement, “yes—rather smoky and robust”.

“That’s a good word”, says Sarah who is standing at the front, leading the tasting. “Robust. Anyone got any more words… you lot at the back?”

At first glance, this might look like a cheese tasting, but rather than passing platters of cheddar up and down the table, we’re passing platters of grass-fed hogget. Hogget is lamb aged between 12 and 24 months and this tasting evening is part of a new movement that promotes rearing livestock solely on pasture.

I’m in The Table Café on Southwark Street, which is mainly home to eateries for people who are short on time— Eat, Pret, Itsu. Outside there are people in suits and black cabs flying up and down like yo-yos. However, tonight the restaurant is filled with farmers who have left the water-logged fields of Wales and the scraggy fells of Yorkshire to come and have their hogget tasted in the shadow of the Shard.

We’re tasting four shoulders of hogget—from Gloucestershire, Kent, Wales and Yorkshire—which have been simmering away for the last six hours under the watchful eye of Head Chef Shaun Alpine-Crabtree. They are all cooked in the same way and the aim of this evening is to ascertain whether different pastures affect the flavour of meat and whether this group of meat-eaters can discern the difference.

“Terroir” refers to the concept by which food produced in a certain locality derives distinctive characteristics that are related to that place. We talk about “terroir” with wine, cheese, cider, beer, honey and even water, all with subtle differences in maturity, texture and origin. However, there are currently only three options for lamb— English, Welsh or New Zealand. From Kentish chalk grassland to the limestone uplands of Yorkshire, there’s a new movement of evangelists who believe you can taste the terroir in meat too.

“It’s time to treat lamb like we treat wine and cheese”

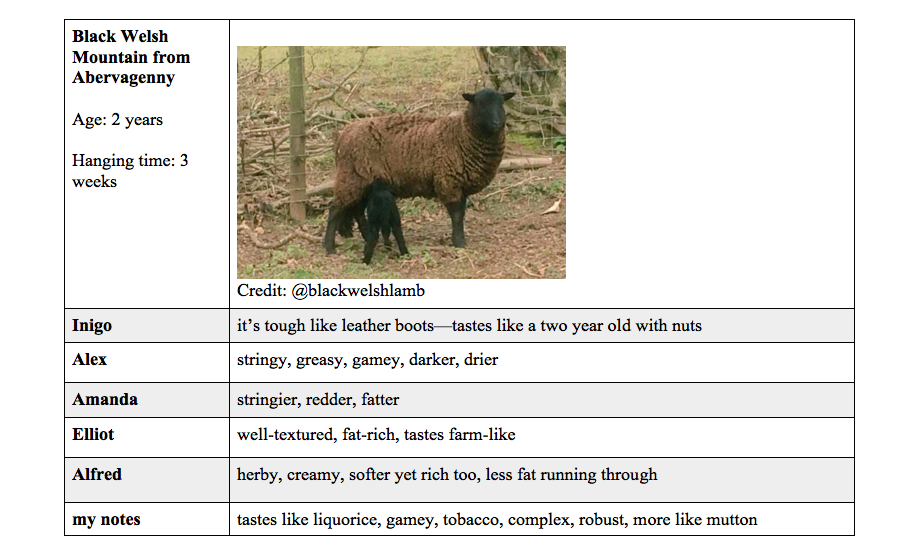

Last year, the Abergavenny Food Festival hosted a “single estate lamb tasting” and increasingly restaurants are putting the finer details on their menus. Consumers want to get an idea of the locality of their meat— the breed, the length of time it has been hung, the age of the animal, the region it is from and its diet.

Created four years ago, the Pasture Fed Livestock Association (PFLA) is at the forefront of this new movement and promotes 100% pasture-based diet through its certification scheme. The PFLA has around 60 certified farmers, 30 butchers and over 200 members (who are mainly farmers), as well as 650 supporters. There are now around 15,000 hectares of land managed under this system of farming in the UK.

“From the luscious Cotswold to the lean, complex black Welsh mountain to the lofty, hard Hardwick to the nimble Swaledale, it’s time to celebrate difference”, says Nick Miller, a Welsh sheep farmer, who introduces the evening. “We need to think about breed, pasture and husbandry. It’s time to treat lamb like we treat wine and cheese.”

When I arrive I’m greeted by a platter of forty raw radishes. If I hadn’t pre-paid for the evening this might have been my cue to run. However, I hang on in there and before I know it I have radish greens in one hand and a watermelon cocktail in the other. The first person I meet is a farmer called Roland Pritchard from North Gower in Wales who has come to London especially for the evening. He’s wearing a shirt with “Gower Salt Marsh Lamb” embroidered in italics above his pocket and has a melodic Welsh lilt. I introduce myself and explain that I am writing a piece about this evening. Rather than seeing this as an opportunity to talk about his meat, the conversation takes an unexpected turn. “My son’s looking for a girlfriend, how are you fixed?”.

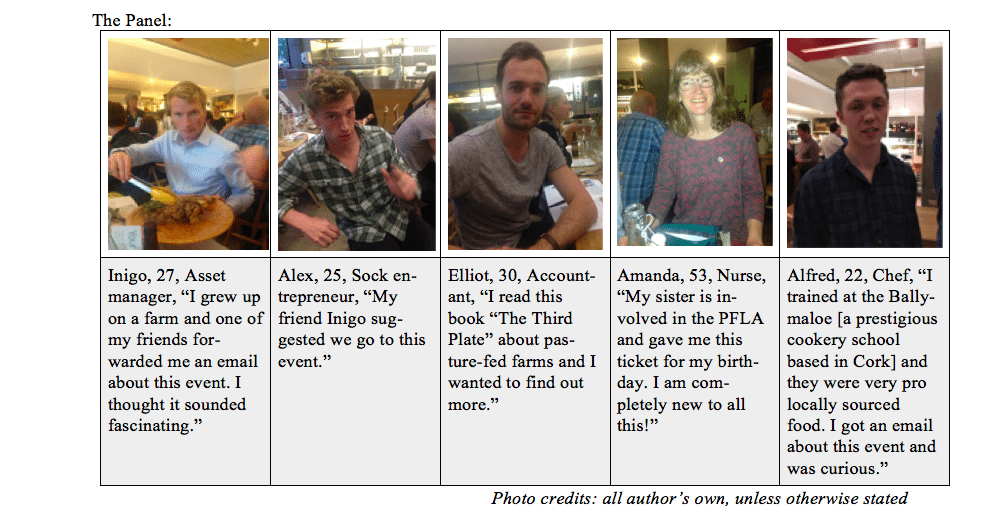

There are about 50 guests, seated on six long tables. The other people sitting on my table kindly agree to be involved in my tasting experiment. Unlike wine tasting, the art of hogget tasting is completely undeveloped, and we’re a bunch of complete novices trying to learn the language of lamb. Armed with pencils, an information booklet on the farms and a box for tasting notes underneath, the evening begins. Nick’s partner and fellow sheep farmer, Sarah Dickens, is leading the tasting and introduces our first farmer, Jonty from Gloucestershire.

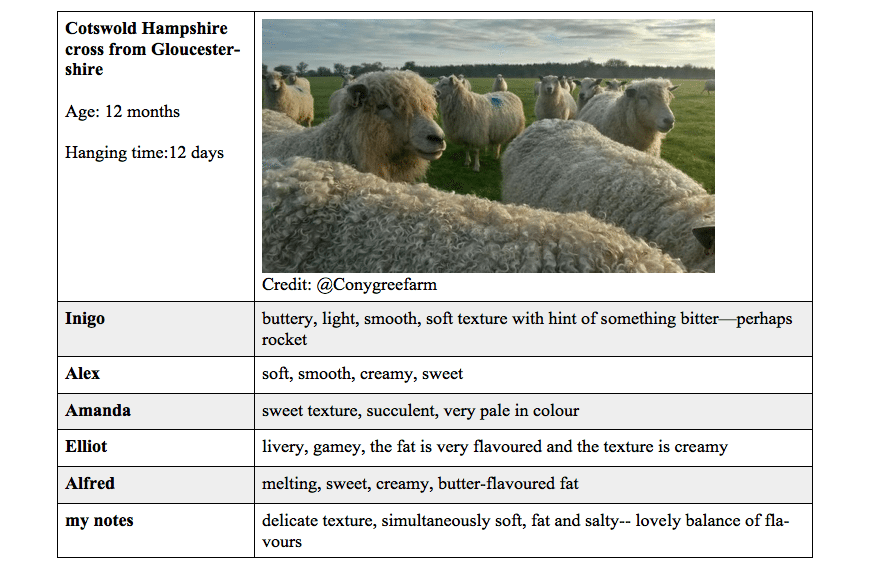

“My sheep are like labradors”, says Jonty, who farms in the Cotswold “they’re really steady and a bit dopey… and they die easily.” The Cotswold is a slow-maturing long wool breed, famous for their curly golden fleece. Due to a decline in the wool trade, numbers have declined rapidly in the 20th century and were close to extinction. However, renewed interest in heritage breeds has led to a — somewhat modest— revival and there are now 2,000 breeding females.

Jonty gives us a textured description of his sheep which graze on sandfoy, ribgrass, self-heal, birdsfoot trefoil and various other grasses I’d never heard of. His “species-rich meadows” contain between 60-80 species of grasses and herbs and their names are littered with references to historic and bygone features of rural England. I am filled with reassurance about the flavour of Jonty’s hogget.

“They’ve been rooting up different nutrients and tastes that are all going to be in the meat you eat tonight”, he assures us. Jonty is also a lecturer at the Royal Agricultural University and director of PFLA. He speaks with obvious affection about his work; “There is a real movement here— re-learning the old skills of grassland management is crucial.”

The hogget passes down the tables with a small pot of well sautéed potatoes. Mint sauce is also passed along until Roland (the matchmaker) loudly says that if you appreciate lamb you won’t need mint sauce with it. Clearly in the company of purists, I tactically position one of the sautéed potatoes over the generous dollop sitting on my plate.

The meat is creamy and the abundance of fat means that even after being cooked for six hours it has remained moist and has a lovely salty finish. Jonty’s golden-fleeced herb-eating hogget tastes as luxurious as it sounds.

“It tastes like millefeuille”, says the lady at the end of our table. “It’s creamy and buttery— almost fragile”.

“Good words!” says Sarah, “anyone else got more words…you lot at the back?”

The discussion branches into many tiny conversations. There is something surreal about people discussing forkfuls of meat with such earnestness. “It’s smooth and then it almost gets slightly bitter at the end”, says Inigo. Alex nods in agreement, “I’m getting herby”, he says confidently. Alfred the chef seems to be the most sceptical on our table: “Isn’t that because it was cooked in butter and rosemary?” he comments. Perhaps it’s not those lovely ancient-sounding herbs we have to thanks but a knob of butter and a sprig of rosemary?

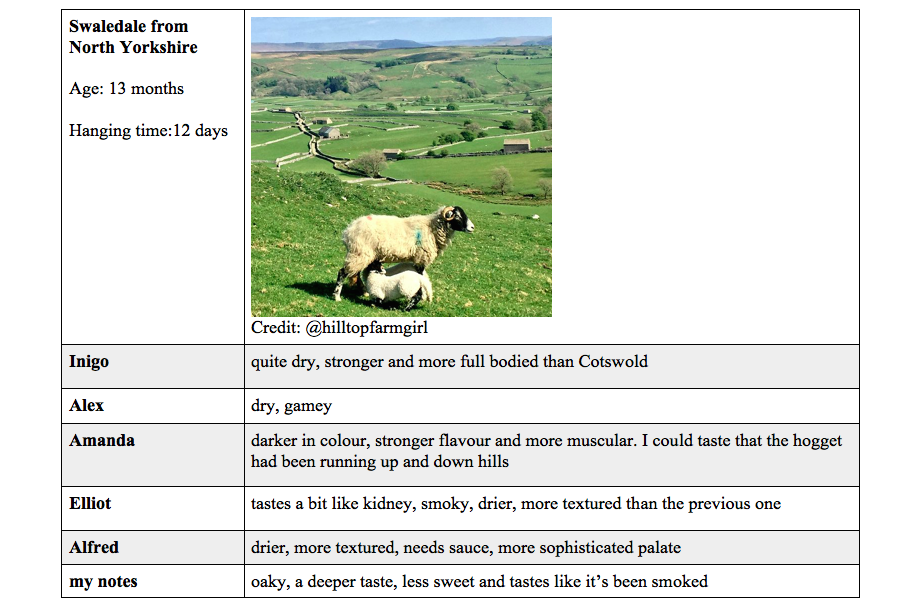

Next up is Neil who farms in Malham, in the Yorkshire Dales. The farm has been in the family for four generations but pasture-fed hogget is a new product. His wiry brown hair looks like it has been gelled down especially for the occasion. Polished shoes and an ironed, checked shirt have replaced the woolly jumper I see on his Twitter posts. He looks slightly uncomfortable in his new setting.

Next up is Neil who farms in Malham, in the Yorkshire Dales. The farm has been in the family for four generations but pasture-fed hogget is a new product. His wiry brown hair looks like it has been gelled down especially for the occasion. Polished shoes and an ironed, checked shirt have replaced the woolly jumper I see on his Twitter posts. He looks slightly uncomfortable in his new setting.

“Paint a picture for us Neil, tell us where you are”, says Sarah.

“My sheep aren’t swanning around like Jonty’s”, says Neil. “They live between 1,200–1,800 feet and graft away at anything they can get between the rock and lichen.” Through winter Neil’s sheep feed on hay from the farm and then are finished on species-rich spring grass, “not that we’ve seen much of that up North”.

His hogget— richer, more aromatic and muskier. It had a less lingering taste and was drier than the Cotswold. The lady with salt and pepper hair was again the first to pipe up with a suggestion; “the colour is very different and it tastes earthier…. more rugged”.

“Like the landscape!” offers her neighbour, keen to make the connection between its upbringing and taste.

Whether it was due to the scarcity of pasture up north or other factors, the two samples did seem to taste significantly different. This hogget is leaner and by common consent it is because it had been scaling the dales. It seems to make sense— exercise deepens the flavour and also creates space within the muscles for fat to build up. This integration of fat into muscle creates a richer meat. Shaun, the head chef, explains that “although these pieces of meat are similar cuts and similar weights, they act significantly different when you cook them”.

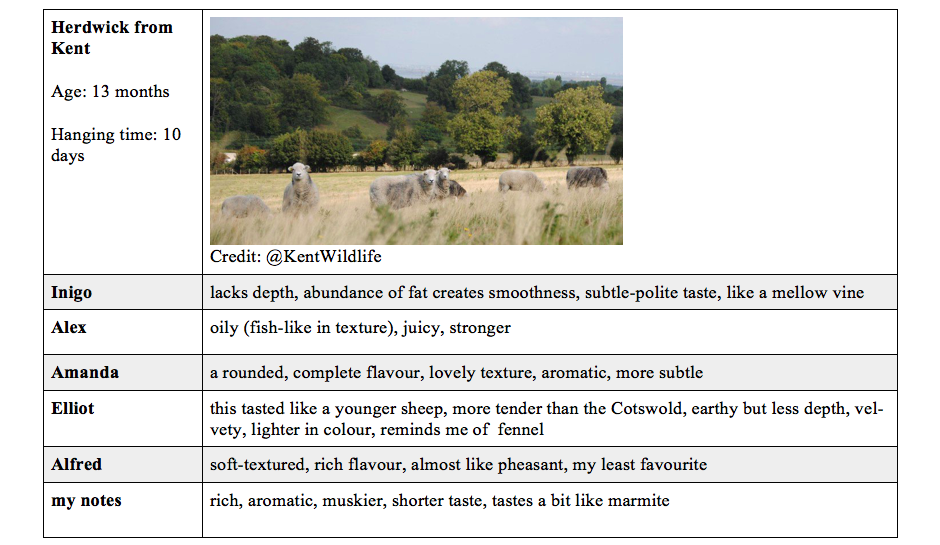

Fidelity Weston introduces the Herdwicks of Kent who are managed by the Kent Wildlife Trust. Herdwick sheep are well suited to conservation grazing and the meat they produce is a by-product of the nature reserve’s management for wildlife. As well as grazing species-rich chalk grassland, these Herdwicks nibble woody species such as bramble and hawthorn, therefore keeping denser vegetation at bay.

“Now these sheep are out of kilter in that they are not in their natural environment”, she explains. In the aftermath of the foot-and-mouth outbreak in 2001 there was an active effort to move Herdwicks — traditionally located in the Lake District— around the country so they wouldn’t be wiped out in case of another disaster.

“I guess they’ve accumulated so much soft fat because they’re a mountainous breed now living a life of luxury down south”, says Amanda.

We discuss the power of suggestion in influencing the flavours we find in the meat. Elliot says he thinks it would be better to hear the farmers’ comments at the end therefore meaning we would have a less biased interpretation of the taste. Alex disagrees, commenting that “If you’re thinking about these stories it makes the meat taste objectively better. Your mind is thinking about these images and pictures that are associated with the lamb.” If you think about other products with “terroir”— cheese, wine, cider— they’re all telling stories too. Perhaps weaving narratives into our food is all part of the experience.

The last one is Nick and Sarah’s hogget— a small, active sheep which grazes on the foothills of the Black Mountains. “We have very bad winters and our sheep lose a huge amount of weight during the winter”, Nick explains that the hogget we’re tasting tonight is a two year old uncastrated male, born in April 2014, killed on April 2nd 2016 and hung for nearly three weeks. Apparently we should therefore expect to see more muscle and a bit more texture.

Unusually for sheep farmers, both Nick and Sarah are vegetarians— Nick has been since 1978 and Sarah nearly as long. Although their vegetarianism started due to concerns about traceability, Sarah says she’s now not eaten meat for so long it is now “too rich and makes me feel sick”. The couple judge the success of their meat by sight and smell.

“It tastes like liquorice!” someone shouts. There is an echo of agreement. “I guess keeping the balls on has given it a much stronger flavour”, says Inigo. The fact it still has its testicles dominates conversation. Someone just shouts out “it tastes of testicles!” without further qualification. My neighbour, who is a farmer, tells me this is not just an excuse to be juvenile, the testicles would make a significant difference to the taste. I wondered if anyone had actually consumed a testicle before. However, I concur, it did taste rather robust.

Hogget eaten in May and June is generally sweeter in flavour and then tastes leaner later in the year as the nutrient-depleted autumn grass comes through. I spoke to Jonty afterwards who said he thought his Cotswold hogget was slaughtered a month too early; “I really wanted to give them that little bit more time”, he explains. Rather like annual variations in wine from the same vineyard, so too the cold spring in the Yorkshire Dales affects the taste. Alfred, the chef, explains that “the seasonal variation in flavour is a particularly British selling point, and one that most farmers are yet to capitalise on”.

Head Chef Shaun explains to me; “There’s something wonderful about meeting the people who look after and safeguard our land— our heritage— and sharing the food here all together. This is principally what food is about.”

“I was initially skeptical when the PFLA approached me about doing meat tasting evenings, like I think most chefs would be. But I’m such a convert. So often we eat food without thinking about it and tonight there’s been some great discussions. It’s so refreshing,” explains Shaun.

I can see the reasons a consumer would want pasture-fed meat, but I’m curious why farmers would bet their livelihoods on such an embryonic market. Roland tells me about his salt marsh lamb from North Gower. “It started 12 years ago when we were selling our lamb to the Common Market”, he says “and we were only making £15 or £20 a head. A lot of our friends said there was salt marsh lamb in France and we could be doing better marketing it as such, so we did and now we’re sending it all over the country and doing well off that.” Salt Marsh lamb in France from the Somme region has received the much coveted French AOC label— commonly associated with wine and cheese production— meaning there are strict guidelines on how it can be produced.

Jonty says he would lose money if he sold it to the supermarket, but can make a bit of money if he sells directly to the consumer— “not everyone buys on price and the people that buy from us want different things”. These farmers are selling directly to people who know where the meat comes from, rather than selling them as untraceable commodities to the supermarket.

Like Nick and Neil, Jonty also get payments from the EU for managing their land for wildlife and receive Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) grants that might not be open to other farmers. Combined with the Basic Payment Scheme, a medium sized wildlife-friendly farm of 100 hectares would get about £30,000 annually in payments from the EU.

I leave the shadow of the Shard and venture into the Kentish countryside to visit the Herdwick and their wildlife-rich meadows for myself. It’s May and the countryside is awash with different shades of green— new leaves next to evergreens, blossom of different colours and the horse chestnut trees decorated with white and pink candles. I can’t remember the hawthorn bushes ever looking so much like thick snow.

I meet Dave Hutton and Mike Keeley; Dave manages the grassland and Mike is in charge of the sheep. Mike drives us slowly through the herd in his Landrover. The field is filled with buttercups and the little white faces of small, curious sheep. I’m told there are 300 of them in all.

Mike explains that they would be finishing their Herdwick hogget on pasture regardless of the PFLA scheme. The sheep here are primarily for conservation and grazing them on this low quality grassland is crucial as it means there is space for the wildflowers to come through. Commercial breeds— i.e. non traditional breeds— would not do well on nutrient-poor grassland. As Mike explains, “our sheep are primarily a tool for conservation, the meat is a by-product”.

We turn off the engine and hear a continuous stream of bird song come from the trees and the occasional bleat of a lost lamb. Dave is keen to see how the wildflowers are getting on. At first glance it just looks like grass with the odd sheep dropping and tuft of wool. However, squatting down next to Dave I can see little green shapes emerging among the grasses. In a month the valley will light up with wild flowers and industrious insects keen to take advantage of the window of warmth.

Mike’s agricultural background is in the Livestock Market where he says he’s “never heard a whisper about pasture-fed meat”. Mike is unconvinced that a large commercial farm can make money finishing meat on pasture. I put this theory to the test and my next stop is to a commercial farm of 1,000 acres that does not receive any government payments for wildlife management.

Court Farm in Kent is run by Andrew Lingham and has been in his family for more than 150 years. I drive up the heavily potted track into the yard where I park the car and my eye follows signs to a farm shop. Just under the barn next door are signs that say “Votes for Women!” attached to scarecrows. Inside the farm shop there are paintings by a local artist, newspaper clippings on the walls, walking maps, baskets of unwashed potatoes and a poster advertising the spring party barn dance— “£10 a ticket for the Hot Rats & the Hartley Morris Men”, to be hosted at Court Farm. The space is speckled with creativity and productivity.

The butchers is at the far end of the farm shop. When I arrive Billy Reid is hand-rolling ‘faggots’— balls of minced pig’s heart, liver and belly fat. “I won’t shake your hand”, he says wryly.

Billy sells Andrew’s meat in Blackheath and Woolwich market in south London at the weekends. The meat he butchers is almost all pasture-fed, the majority of which comes from Court Farm. After drying his hands on his white overalls he hands me a cup of builder’s tea in a chipped white mug.

“About a year ago people started asking me about whether the meat was grain-fed or grass-fed. Gradually numbers have been increasing and now I reckon around 5% of customers will ask. They associate grass-fed meat with being better quality than their grain-fed counterparts.” Scientists say it is higher in Omega 3 and 6, has more minerals, less of the bad fats and more of the good ones that we need in our diets. Billy says he hasn’t yet been pushing his meat as pasture-fed and thinks there’s a growing market for it.

Further up the hill is Andrew’s office, which is piled high with papers, obscuring half of the window that lights the room. “So why do you do 100% pasture-fed?” I ask. He sighs loudly, like you would expect from a man with so much paperwork. “Where do I begin?”

“I have been finishing my livestock on cereals and it wasn’t working— I was losing money year on year. Simple as that. For this farm to stay afloat and for me to make some money out of it, I’ve got to be able to take the costs out of it. And going into pasture was the way forward for me, it’s more efficient. This is my first winter finishing lamb without using cereal.”

He paused. “And how did that go?” I ask.

“Yeah, you know what, I think we’ve made some money”.

For Andrew, finishing his livestock on pasture has reduced his overheads as he has not had to plant and harvest grain for animal consumption. The traditional breeds are hardier and can stay outdoors all year around and the carcasses still reach a similar weight. He says regardless of the PFLA, he would be rearing his livestock on grass because he can fundamentally produce better quality meat more cheaply.

This decision points to problems in the industry more broadly. “We’ve complicated farming and agriculture too much. We need to improve how we work with nature and work the land rather than spraying chemicals and always working against it. We’ve taken the skill out of farming that we had from our fathers and grandfathers and forgotten it. Using a can of spray is too easy, we need to re-learn management skills.”

Not only does Andrew believe he can produce his lamb more cheaply pasture-fed, but he claims using too many fertilisers is a “false economy”— in the long term he believes soils will actually be more productive. The transition from small traditional farms into larger more intensive ones has led to traditional practices such as crop rotation being replaced by the use of chemical fertilisers.

Last year he made the switch and is already making more money than when he finished his livestock on cereals. “Conventional farmers still think we’re a bunch of nutters, pure and simple. At some point the public need to pick up and run with it. After that, I’m convinced other farmers will follow suit.”

I ask Andrew if he thinks grass-fed meat might taste better than meat that has been corn-fed. He says “the jury’s out, but it’s definitely a different flavour”. For him, as with many pasture-fed farmers, part of the motivation for selling pasture-fed meat is to avoid selling it on the open market and being subject to the mercy of supermarkets. Andrew can get a better price selling local from his farm shop.

Not only is there a movement for farmers to grow grass-fed, but this is in part fueled by increasing consumer interest in the benefits of grass-fed meat, both in terms of heath, the environment and animal welfare. As seen from the tasting, the notion of “terroir” in grass-fed hogget seems fairly convincing. Not only do we have meat on our plates but the depth of the nation’s heritage too. Jonty, farmer and lecturer at the Royal Agricultural University, likens the PFLA movement to “the revolution that organics was 30 years ago”. The PFLA has been going for four years and already there is a growing number of meat evangelists. Although I’m certainly not well-versed in the language of lamb, perhaps a future for single-estate, pasture-fed hogget is not as distant as we might think.

Graham Harvey’s last book “The Killing of the Countryside” won the BP Natural World Book Prize. His new book, “Grass-fed Nation”, released last month, lays out the argument for grass-fed food. The agricultural story editor of The Archers talks to me about why grass-fed farmers hold the key to our heritage.

Lamb is not just lamb. All those species of grass will be contributing different things, all of them will have some influence on the composition of flavours, it couldn’t be any other way. I wrote my book “Grass-fed Nation” because I think the only thing limiting the sale of really good food is public understanding. As a pasture-fed farmer, once you get your story out you have customers for life. The problem is the whole supermarket model depends on food being a commodity. Pasture-fed farmers are removing their food from the commodity market.

In my book I write about working on the Thames Valley farm as a student in the 1960s. I thought the rich and creamy milk produced by that pastoral landscape was as distinct as the terroir of any French wine or artisan cheese. I guess the flavour of that milk was partly in my head. I’d spent the summer seeing how the cows grazed and the pasture they were on. The experience of being on the farm was all part of the taste. These stories are so important. From a marketing perspective, having a customer who understands the stories and can make a link between the land and the flavours is a brilliant advantage.

I used not to not be able to talk at farmers’ meetings without getting booed, but farmers are more open to talking about grass-fed. It’s becoming increasingly apparent that high-input systems are unsustainable. I’ve written about farming since the 1970s. I am an optimist now, or at least much more so than I was 10 years ago. The public are still convinced by modernistic stuff, but increasingly farmers are realising we must get back to a more ecological approach to farming.

The Pasture For Life Association (PFLA) are ahead of the game— they’re still an embryonic institution but they’re producing something better. I grew up on a council estate in Reading and our milk came from a local dairy. The farmer set it up between the wars when prices slumped and he was forced to become entrepreneurial to survive. By the 1950s he was selling to half the town. For 50 years farmers have been protected, but part of me thinks it needs to get really hard for them for change to happen. Our current farming model has to break down and something’s got to go in its place. Sooner or later today’s farmers will have to go out and sell it direct. Now that will be a great thing.

All these environmental schemes are there because production is seen to be at odds with nature. The notion that you either have a lot of food or biodiversity, but not both, is hugely oversimplified. Higher Level Stewardship payment, which rewards farmers who make active environmental management practices, is necessary at the moment, although I do think in the long-term the system would be better with no subsidies at all. It may be naive of me, but if you have a pasture-based farming system you get lots of biodiversity without having to pay. Taking small bits of land out of production and creating spaces for wildlife is window dressing— if you had the right production system you wouldn’t need to do that.

I was interviewed by a food journalist last month who asked me if this was “another guilt trip”. It is completely the opposite. We’ve eaten pasture-fed meat for thousands of years, this is not some reaction to “clean eating”, it’s what this island of ours does.

There’s an explosion of cooking books but they all start in the wrong place. Food doesn’t start in the kitchen but on the farm, and we must link up our food with the wildlife and social history of that land. For example with National Trust properties, instead of just marketing the house, we should be marketing the grassland and the food it’s producing. These grasslands also have wonderful stories and are part of our heritage. When you buy the food you become part of that ecosystem. It’s as authentic as you can get.

Farm Websites:

Further reading

Pasture For Life: “It can be done”

http://www.pastureforlife.org/news/pasture-for-life-it-can-be-done/>

PFLA website:

http://www.pastureforlife.org/

PFLA forum:

Talking grass:

http://www.talkinggrass.co.uk/pasture-fed-livestock-association-ready-farmer-members/

Comparison between grain-fed and grass-fed meat:

https://extension.usu.edu/files/publications/publication/AG_Beef_2011-01.pdf

Telegraph: “Forget free range: Is grass-fed and pasture-raised better for animals, industry and us?”

Telegraph: “Whatever we do, shops tell us to be cheaper: the growing crisis in Britain’s farms”