James Friend considers the importance of local grain economies to enlightened bread-making and explores what determines the quality of bread, and why quality matters in terms of health, flavour, environmental and community benefits.

Give us this day our daily bread

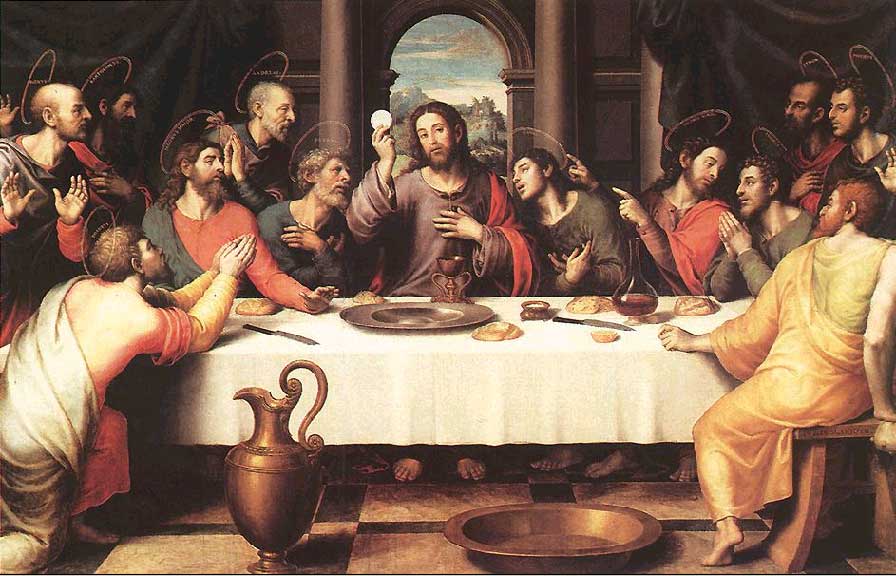

Our dependency on bread for sustenance is ancient and our relationship with it is even considered holy. As highlighted in that famous line, ‘our daily bread’ is synonymous with nourishment, a staple food which is still a major part of our diet, with the equivalent of 12 million loaves sold each day in the UK. (1) The breaking of freshly baked bread used to be considered an act of fellowship, with the origins of the word ‘companion’ roughly translating from com panis as ‘with bread’ or ‘bread fellow’. This sharing of bread was once used to nourish both the individual as well as friendship.

Yet what we once called bread has changed significantly over the last couple of centuries. More recently the production methods adopted for mass consumption have created products with little regard for health and flavour. The current quality of bread means that the digestibility and nutritional benefits are being called into question with the rise of various protein intolerances (such as gluten), as well as an overall decline in the quantity of minerals and vitamins. (2) There are some who are advocating enlightened bread-making, not only to counterbalance the rise in gluten-free products and the falling rates of bread consumption in recent decades. These pioneers are motivated to re-establish quality bread that is beneficial in terms of maximising the health of individuals, local communities and the environment.

Real bread deserves real flour

The majority of modern bread-making pays little regard to its nutritional qualities or the environmental and social impact of production and distribution. Andrew Whitley, author of Bread Matters and co-founder of the Real Bread Campaign is raising awareness of this, calling for:

“Real Bread that [is] made without the use of processing aids or any other artificial additives” – Real Bread Campaign

This seems like a simple request for untampered bread made from only the essential ingredients of flour, water and yeast (and perhaps salt). Yet it is important to question why additives are being used; what might be lacking, or what improvement is trying to be made. To understand why this unnecessary adulteration might occur requires looking back through history.

The desire for refined white flour was a result of the development of roller milling and sifting in the 1800s. Whereas stone-ground milling simply grinds grain whole between two stones, roller milling filters out the husk, germ and pulverises the endosperm, leaving basically white starch (with the nutrient-rich brain often fed to animals). This results in a significant amount of nutrients being removed from the grain, between 41 to 92%. (3) White flour is so deficient in key nutrients that since 1953 it has been fortified with synthetic iron, calcium, and two B vitamins (thiamin and nicotinic acid). (4)

Furthermore, as production demands on bakers increased during the industrial revolution, flour became fortified with other ingredients to ‘improve’ the whiteness of refined flour. This meant bakers could reduce costs by using less expensive flour which included ground rocks such as chalk or alum (potassium aluminium sulphate). Reducing quality and adding hidden ingredients to meet required demand and a lower price may seem odd, yet it is worth considering the situation in more recent times – horsemeat anyone?

‘The addition of chalk to bread was officially recognised as adulteration and banned by law: today in the name of ‘fortification’, it is mandatory in almost all loaves in the UK’ [to ensure the flour meets required calcium levels] – Real Bread Campaign

In an attempt to reduce birth defects related to pregnant women not receiving enough folate, the UK government is considering making it law to include synthetic folic acid in all UK flour (after pressure from the Scottish government). Perhaps it is at this stage that we acknowledge the importance of nutritional quality when processing food, and realise that refining and replacing nutrients makes little sense; why not leave it unrefined (and untreated with synthetic additives) as this would naturally retain more folate, or better yet, increase the folate two or three fold through proper fermentation. (5)

Fermentation – Slow is better

Traditional leavened bread-making has always occurred with natural fermentation as part of the process, and there is evidence to suggest that long-duration fermented sourdough is more likely to reduce intolerance or even be ‘gluten safe,’ due to breakdown of offending proteins.(6, 7, 8). Therefore, if you stay clear of bread altogether for heath reasons, it might be worth sampling some of the wide variety of sourdough loaves (the longer fermented the better), each with their unique flavours.

“The sour in sourdough is a by-product of the bacteria in the dough. This bacteria create organic acids as they feed on naturally occurring sugars; by controlling the time and temperature the dough is proved at, the baker determines the flavour of the bread. At the right concentration this acidity is delicious and also preserves the freshness of the bread.” – E5 Bakehouse

You can try making your own sourdough using this recipe, or look out for it at your local bakery which might run classes (if in London, Today’s Bread, the Dusty Knuckle, and E5 Bakehouse are good places to start.)

In contrast to properly fermented bread, since 1961, a method of making bread known as the Chorleywood Bread Process (CBP) was devised which uses high speed mixing combined with additives to produce a slurry dough. This can then be baked to form a voluminous and light bread without any necessary fermenting time. A typical burger bun or sandwich will most likely have been made using the CBP, and will stay soft until the preservatives no longer prevent mould from growing. The majority of the UK’s bread is made this way, around 80% in 2009. Significantly, although additives used in this process have to be labelled by law, enzymes do not, as they are deemed ‘processing aids’. These are added to make lighter bread (which holds more gas) and make bread stay softer for longer. The lack of enzyme disclosure matters because many can be allergens, and the provenance remains hidden as they can be derived from animals or even genetically engineered.

Heritage grains

Alongside the innovation in bread-making over the past 50 years has been the intensification of wheat growing to increase yields. Starting in 1908 and intensifying as part of the ‘green revolution’, wheat has been hybridised, for example with shorter Japanese varieties to create dwarf-wheat. This allowed cultivation in partnership with sprayed inorganic fertilisers (without it falling over) and herbicides (as it no longer shaded out weeds). These modern varieties may be high-yielding, but were not grown with flavour or nutrition in mind, and as a result older varieties contain significantly greater micro-nutrients (and less intolerance triggering compounds).(9)

Growing heritage varieties with less intensive agro-ecological principles allows less competition between plants for available resources due lower plant density. This not only has positive effects on nutrition, but allows larger and more robust root systems, increased drought resistance, and maintains the genetic diversity of crops. (10). Promoting rare and older varieties of wheat is not only important for nutrition, but to maintain genetic diversity of crops. There is currently heavy reliance upon very few varieties which is not ideal for disease resistance. Encouraged by the National List (11) (which all cereal varieties must be on to be eligible for certification and marketing in the UK) there is only one spring wheat variety ‘Mulika’ which is recommended as the highest yielding and best for baking (deemed ‘group 1,’) which as a result dominated 60% of the market share in 2016. (12)

Pioneers

The pioneering Bread Lab in Washington State University was established as one of Dan’s Barber’s ‘grain heroes’ Steve Jones, a grain breeder, refused to grow RoundUp-resistant wheat for Monsanto. Working instead for the interests of regional farmers, he aimed to grow grains with a compromise between yield, resilience and, most unusually, nutrition and taste. Trials including heritage (pre- ‘green revolution’) grains resulted in an interesting comparison of the varietal performance within the differing regions of the Northwest, similar to the associated ‘terroir’ regions with wine.

One such isolated region is the island of Lopez in the San Juan Islands where a farmer, baker and old-machine collector came together with the goal of establishing island grown grains that are threshed, milled and baked for the island community. After sourcing small packets of rye, barley and wheat and multiplying the grain successfully over 4 years, they had enough to start baking in their wood fuelled oven with local island grain. The first public tasting session was well attended despite a frosty morning, with an interested and engaged community eager to taste the 24 varieties of deliciously distinct bread.

In times gone by, the community hub was based around grain in the form of the bakehouse and brewhouse (which often supplied yeast in a mutual relationship). These places were visited on a daily basis, and the range of businesses reliant upon grain growers extended also to thatchers, millers, and distillers, forming a local grain economy.

Millers The renovation of the Felin Ganol working water mill in Wales naturally led to the search for local grain to be milled and has resulted in the Welsh Grain Forum being formed, a community committed to using and promoting Welsh grain throughout the supply chain from soil to sandwich (or pint!) 150 years ago every community would have had a local mill, and it would have been normal to have local bakers and brewers who would now be considered artisans. It is interesting to see how change can be driven by conscious millers, who usually serve the bakers specific requirements for flour. It seems that if consumers are demanding quality local bread, then the baker, miller and grower will provide, and local grain economies can flourish. Today, there is rising interest in those wishing to connect with the provenance, variety and flavour of grains, evident from the Real Bread Campaign and Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA).

Growers & Brewers

A recent collaboration project engaging 40 co-investors in the growing of heritage grains is the Our Field cereal co-op model. Similar to a cereal CSA in sharing any risk, it aims to encourage farmers to transition to better agro-ecological practices, while re-inventing farm economics and increasing the amount of high quality, milling grade heritage grain grown in the UK. By documenting the process the intention is to provide an open source blueprint that can be shared and replicated to spread the #OurField movement.

Similarly, Grown in Totnes is growing, processing and selling staple cereals within 30 miles of their community that is supporting their initiative. So far they have grown spelt and ancient einkorn grain (first cultivated in from wild wheat in Neolithic times, 10,000 years ago) which they have brewed into a hop-free beer. They have also grown Maslin which is a Medieval blend of wheat and rye, with help from one of the leading figures in the heritage cereal movement John Letts.

Bakers

There are bakers who care deeply about re-establishing flour and bread supply that maximises health, supports local economies and are engaged with their community. The Riverside Bakery is a community supported bakery which aims to co-produce the bread along with its members, who buy ‘bread shares’ for a weekly supply of bread, as well as involvement in the business. Any surplus is given to support initiatives which will positively affect local food production, including Scottish grain growing and milling (prioritising organic and heritage varieties), food education about the importance of real bread, and workshops to empower people in making their own.

A local grain economy can be encouraged by anyone in the supply chain; whether a miller working with growers who believe in the benefits of locally grown heritage grains, a skilled baker experimenting with quality flour and maximising flavour, or a brewer making refreshing drinks. Perhaps most important of all is the engaged consumer who recognises the impact good bread can have on their own health, their community and just how tasty it can be!

Footnotes

1. http://fabflour.co.uk/fab-bread/facts-about-bread/

2. http://www.breadmatters.com/blog/folic-acid-in-our-flour-food-sense-or-counsel-of-despair.html

3. http://wholegrainscouncil.org/files/backup_migrate/WGvsEnriched2011.pdf

4. https://www.sustainweb.org/realbread/flour_fortification/

5 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224405000828

6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19747600

7. http://aem.asm.org/content/70/2/1088.full?ijkey=9ec21f12c3108ac644cb2085608b315ca768450d

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20951830

9 http://breadmatters.com/index.php?route=information/information&information_id=25

10. http://www.shipton-mill.com/the-mill/about-shipton-mill/our-philosophy