Freelance Horticulturalist and Writer Jessica Peace shares her experiences of lambing and re-thinking her relationship with meat..

I haven’t eaten meat or dairy for years, primarily to reduce carbon emissions but there were other reasons; I thought I would avoid poor animal welfare and farming by just cutting out meat and dairy completely. This year I met a couple who mentioned their daughter Jenny was a sheep farmer, I asked if I could stay with them and help with the lambing. What I thought would be sitting with a flask watching for lambs became a new understanding of farming, husbandry and caring for the land. Now I’m toying with this question, is buying small farmed, organic meat and dairy a better fight against bad farming than not buying at all?

Jenny Holden -Credit: Christopher Wilde

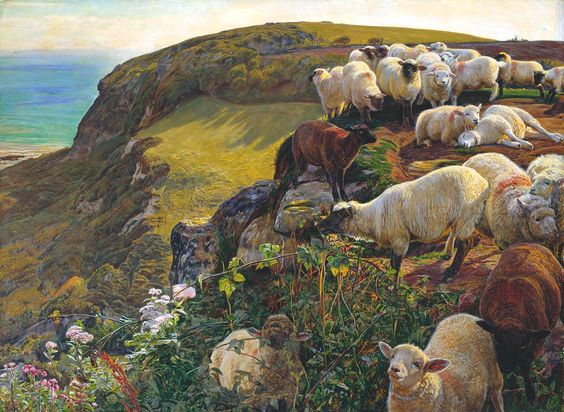

This wasn’t the first time this year I’d had the thought that for a sheep, being killed “compassionately” or stunned and then eaten, might be better than being pulled apart by a fox, or slowly rotting off from untreated disease on the hills. This winter I spent some time tramping across the Yorkshire Moors with my Dad, sometimes through the darkness to get some height before sunrise; as we clambered amongst the Swaledale sheep, I witnessed their extraordinary beauty: their softness and resilience, gentle against the harsh January, lichens crawling up their limbs.

Jenny’s Shetland ewes rested peacefully in a valley of the Lake District, giving birth without need for help the few days I was there. But it was while banging in a fencepost and seeing how fertile the soil was; the wildflowers flickering at the gate, allowed to be there; looking up at the protected marshland, woods and streams just beyond the grazing pastures, that I understood how complete a process farming can be: the peace and protection it brings to the land as well as the livestock. ‘Husbandry’, ‘guardianship’, ‘working the land’: these words taking on a new fullness. As a gardener I’m used to working with the elements but working with animals is a continual, relentless motion. I watched Jenny constantly checking their health; noticing the slightest limp; moving the sheep to good pasture and allowing the land to renew itself; fixing boundaries and chasing out livestock from other farms, concerned with spread of disease. As I watched her call down her sheep from the hilltop I saw the reciprocal respect.

We visited Maria Benjamin and John Atkinson at Nibthwaite Grange Farm, a larger farm where five hundred ewes were lambing; the ewes bearing twins were brought into barns which were clean and warm. Maria pointed to the ‘prolapse spoon’ and referred to the difficulties of lambing and the inevitable deaths. In another barn cows were bearing calves too, just as warm and clean and well fed. I saw how all these farmers were knackering themselves to protect their animals. I sat in the kitchen with them and poured milk in my tea – it can’t be that bad if these lot drink it? (my next research)

Maria Benjamin. Credit: Nibthwaite Grange Farm

Credit: Nibthwaite Grange Farm

Jenny and I talked as we drove about taking sheep to fresh grazing and checking on the ewes. As well as looking after one hundred sheep, Jenny’s an ecologist, lecturer and postgraduate researcher in primitive sheep genetics; she explained to me the issues of large crop manufacturers damaging the soil and spoke of factory farming being both abhorrent and horrendous for the environment.

Since I got back home I’ve been ransacking articles, podcasts, TED talks, youtube videos, sites like the Soil Association, RSPCA, WWF, and The Sustainable Food Trust. In terms of animal welfare and the environment, the problem always seems to be intensive livestock farming and the current and growing demand for meat. It’s the unnessaccary rate of consumption and poor farming practices that are the problem, rarely the small, organic farms. And back to the question I’m rolling over, in a capitalist society where there is no slowdown of cheap meat, If we don’t support smaller farms and allowing them to regenerate the land and give animals a good life, will intensive farming just find a stronger grasp?

I’m hooked on the idea of grass-fed ruminants and their role in soil regeneration and carbon sequestration. The natural effects of ruminant’s grazing, tramping and nutrient distribution, manipulated by the farmer as they rotate the livestock allowing the land to regenerate, carbon to be stored and promote plant diversity. This makes sense to me as a horticulturist, when the practice is carried out on a small scale, negating the use of fertilisers and pesticides and providing the animals with a freer more natural life. Only today I was throwing seaweed on a dry lawn thinking, “this just needs a bunch of sheep stamping on it’. The argument for grass-fed farming is contentious, the recent publication ‘Grazed and Confused’(2017) analyses grass-fed farming in the context of climate change and states, ‘well-managed grazing in some contexts can cause carbon to be sequestered in the soil… But at an aggregate level the emissions generated by these grazing systems still outweigh the removals and even assuming improvements in productivity, they simply cannot supply us with all the animal protein we currently eat.’ Last month’s Indie Farmer published the article ‘WHY WE NEED TO CHAMPION GRASS-FED FARMING’, here Richard Young, policy director of the Sustainable Food Trust threw light onto a lesser talked about aspect of ruminant grazing, “…all the carbon in ruminant methane is recycled carbon – grazing animals can’t add more carbon to the atmosphere than the plants they eat take out by photosynthesis.”

Being human takes a lot of eating. Our bodies need a complex and constant supply of nutrients, many of which can be found in a slab of meat or a glass of milk – but if we’re not getting these nutrients from animal products where are we getting them from? Our plant-milks; meat-alternatives; coconuts and avocados; if not sourced organically and are often impossible locally, could be wrecking soils; full of palm oil; shipped over thousands of miles and produced with poor human rights. It’s easy to approach a ‘meat-free’ or ‘plant-based’ diet with a lack of thought when there has been a societal decision that not eating meat will ‘combat climate change’ or ‘save the planet’. Last year a study published in ‘Science’ journal evidenced, “the impacts of the lowest-impact animal products exceed average impacts of substitute vegetable proteins across GHG emissions, eutrophication, acidification (excluding nuts), and frequently land use.” The study was led by Joseph Poore who claimed, “The reason I started this project was to understand if there were sustainable animal producers out there. But I have stopped consuming animal products over the last four years of this project.” I just find it hard to believe that farming animals without damaging chemicals is worse environmentally than farming crops with; but also it’s unclear if the ‘low-impact’ data was collected from small, organic sites. I am also questioning myself, did I just enjoy working the land and chasing the sheep so much that I’m now up for supporting this way of life?

Sat at home I contacted Jenny and Maria about this article; I asked Jenny about her thoughts from an ecological perspective: “I think it’s important to remember that grazers do have to exist if we are to keep those grassland ecosystems that support thousands of species. Grassland covers much of the earth and we can’t eat grass! Grassland sequesters more carbon than woodland does, especially under drought conditions, which are increasingly common in this country.” Maria explained the process from her own farm, “a beef animal that we graze on our land, when it’s taken off for slaughter, that animal will have helped the biodiversity of the land so you would see no soil devastation. That one cow would feed roughly one thousand three hundred people (a 200g portion of meat). I can’t imagine a plant-based protein for one thousand three hundred people leaving a landscape intact in the way low-impact native cattle and sheep do.”

I came away from The Lakes with gorse splinters; the taste of milk and the sensation of a Teesdale lamb chewing on my finger; thinking of Rosey who wasn’t put into lamb this year, pining amongst the other ewes; thinking of the words ‘less’ and ‘enough’. Eat less and just enough, farm less and just enough.

But eating meat again does require a change in my thinking, the same thread that was formed when I decided not to eat meat will need to be torn and re-woven; if I can believe what I think might be true, that eating meat reared organically might be the best solution at this time for animal welfare and conservation. I have always thought the argument, “if you can’t kill an animal, you shouldn’t eat it” nonsense; but now whether I start eating meat again or not, I don’t think I’ll ever fully be convinced until I’ve reared an animal, taken it to slaughter and eaten it. Twin lambs were born on my last morning, two barely perceptible smudges clawing and stumbling by their Mum, sheltering from the cold by the dry-stone wall. They named one ‘Jessica’, perhaps I’ll eat her.

More Information

Jenny Holden and her Shetland sheep: https://www.facebook.com/SmaliShetlandSheep/, https://wildeecology.co.uk/category/conservation-grazing/.

For more information on Maria Benjamin and John Atkinson at Nibthwaite Grange Farm, including Honeysuckle the cow and Maria’s Soap Dairy:

@dodgsonwood, https://dodgsonwood.co.uk/.

Jessica Peace is a freelance horticulturist and writer.